How to model dwell time of proteins on DNA binding sites in R - part 1

July 19, 2014Disclaimer: In this post i’m working through my own thinking on how to think about and model simple dwell times of proteins on their DNA binding sites. I’m not sure any of this is correct (yet).

Statistical interpretation of protein dissociation

Let’s consider an individual protein bound to DNA that is observed at fixed time

intervals of \(t_i = 0.1s\) by single molecule imaging. At each of these

steps there is a certain probability \(p_d\) that the molecule dissociates from

the DNA. This can be modelled as a bernulli process that is repeated

until one decay event (i.e. dissociation) has been observed, which means that the

number of time steps until dissociation should follow a negative binomial

distribution with a “success rate” (i.e. probability of staying bound)

of \(p_{nd} = 1 - p_d\).

The mean of the negative binomial distribution is

\[\mu = \frac{p_{nd}}{1-p_{nd}}\].

Therefore, if a protein has a mean dwell time of 10s at a given

site, the probability of dissociation during any time step \(t_i\) would be

\[\begin{aligned}

\frac{p_{nd}}{1-p_{nd}} &= \frac{10}{0.1} \\

p_{nd} &= \frac{100}{101} \\

p_d &= 1 - \frac{100}{101} \approx 0.0099 \\

\end{aligned} \]

Similarly, for a mean dwell time of 1s, \(p_d \approx 0.09091\).

Simulating a single high affinity site model

Based on the previous section, dwell time data can now be modeled for a single high affinity site with a mean dwell time of 10s and a total of 2000 bound sites (without actually using the neg. binomial distribution). A term for measurement error is introduced as well.

set.seed(13219)

dt.1 <- c()

ti <- 1

n <- 2000

pd.ha <- 1 - 100/101

while (n > 0) {

n.diss <- min(sum(runif(n) <= pd.ha), n)

n <- n - n.diss

dt.1 <- c(dt.1, rep(ti, n.diss) + round(rnorm(n.diss, sd=2)))

ti <- ti + 1

}

dt.1[dt.1 < 1] <- 1

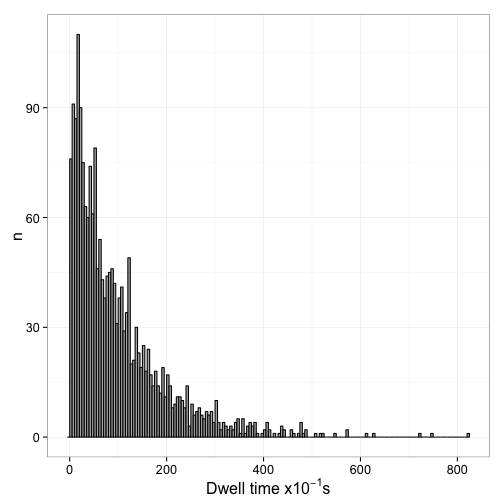

Plotting the distribution of dwell times

library(ggplot2)

p <- ggplot(data.frame(dt=dt.1)) +

geom_histogram(aes(x=dt), fill="grey70", color="black", binwidth=5) +

labs(x=expression(paste("Dwell time x", 10^{-1}, "s")), y="n") +

theme_bw(16)

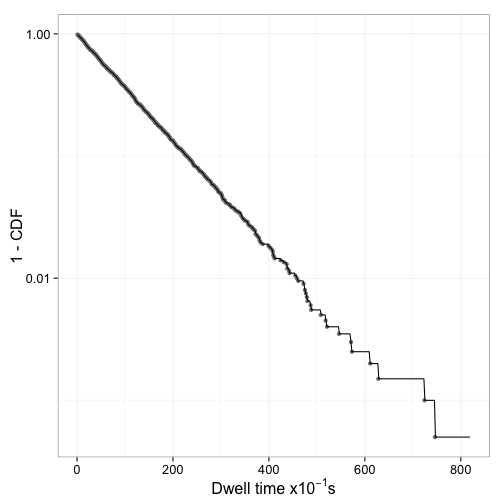

Now we can interpet this from the view of the whole population of sites. Essentially, unlike what happens in the single molecule tracking, we assume that we started with all sites bound and then observe the decrease of bound sites over time. This is equivalent to shifting all dwell times overved at different times in the experiment to a start time of 0. The easiest way to do this is essentially calculating an empirical CDF function of the dwell times:

dt.1.cdf <- ecdf(dt.1)

Next, we create a data.frame that gives unique values of dt.1 along

with 1 - CDF (unique values only since there are many ties in the

data).

dt.1.u <- unique(dt.1)

dt.1.df <- data.frame(t = dt.1.u,

mcdf = 1 - dt.1.cdf(dt.1.u))

dt.1.df <- subset(dt.1.df, mcdf > 0)

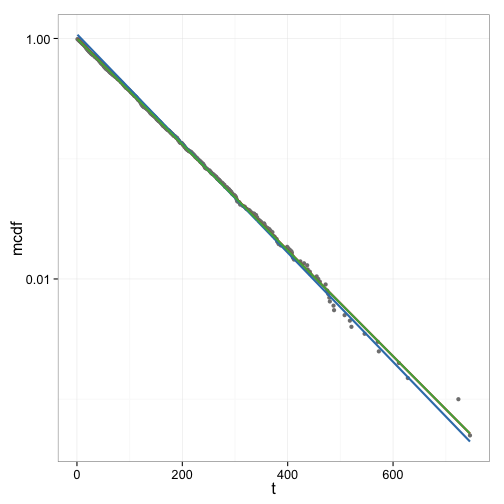

Figure 2 shows that 1 - CDF indeed appears to be an exponential decay.

Fitting a single exponential model

Linearize data and fit by linear regression

The exponential decay function

\[n(t) = n_0\cdot e^{-\frac{t}{\tau}}\]

where \(\tau\) is the mean dwell time can be linearized

\[\begin{aligned}

log(n(t)) &= log(n_0\cdot e^{-\frac{t}{\tau}}) \\

&= log(n_0) - \frac{1}{\tau} \cdot t \\

&= log(n_0) - \lambda \cdot t \\

\end{aligned} \]

and the linearized model can be fit to transformed data:

dt.1.df$log.mcdf <- log(dt.1.df$mcdf)

linm <- lm(log.mcdf ~ t, data = dt.1.df)

summary(linm)

## Call:

## lm(formula = log.mcdf ~ t, data = dt.1.df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.2550 -0.0104 0.0014 0.0143 0.4350

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3.96e-03 3.95e-03 1 0.32

## t -1.01e-02 1.63e-05 -623 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.0425 on 353 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.999, Adjusted R-squared: 0.999

## F-statistic: 3.88e+05 on 1 and 353 DF, p-value: <2e-16

results in the expected mean dwell time of

\(\tau = \frac{1}{\lambda} =\) 98.5474 and

an intercept of 1.004.

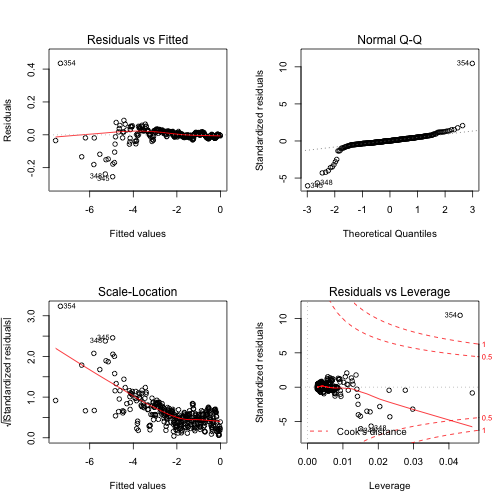

However, the diagnostic plots for the linear regression on transformed data suggest that some assumptions are being violated (see Figure 3).

There are several issues i can think off that may play into this:

- because of the nature of the data generating process, there are many more

data points to the left of

\(\overline{X}\)than there are to the right - the linearization has to assume that the error is multiplicative, but the data generation process has an additive error term

- the data is discrete

- the noise in the data is unrealistically low.

The second and third term cannot be easily fixed. However, what would happen if the 1 - CDF data was replaced by a fixed, evenly spaced number of linearly interpolated data points?

eq.spaced <- seq(min(dt.1), max(dt.1), by=1)

df.eq <- data.frame(t=eq.spaced, mcdf=approx(dt.1.u, 1 - dt.1.cdf(dt.1.u),

xout=eq.spaced)$y)

df.eq <- subset(df.eq, mcdf > 0)

df.eq$log.mcdf <- log(df.eq$mcdf)

linm.i <- lm(log.mcdf ~ t, data = df.eq)

summary(linm.i)

## Call:

## lm(formula = log.mcdf ~ t, data = df.eq)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.423 -0.048 0.007 0.073 0.581

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 8.19e-02 2.06e-02 3.98 7.5e-05 ***

## t -1.05e-02 4.35e-05 -240.58 < 2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.294 on 817 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.986, Adjusted R-squared: 0.986

## F-statistic: 5.79e+04 on 1 and 817 DF, p-value: <2e-16

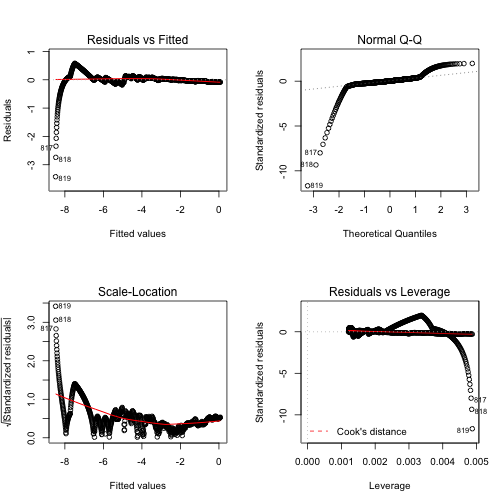

Figure 4 shows the diagnostic figures for this fit. This certainly didn’t help any.

Directly fit exponential model

In our specific case, since we are studying a CDF, \(n_0 = 1\), which

means that the exponential that we are fitting is

\[n(t) = e^{- \lambda t}\]

We fit this to the original data using the base R nls function

expm <- nls(mcdf ~ exp(- l*t), data=dt.1.df, start=list(l=1/5))

summary(expm)

## Formula: mcdf ~ exp(-l * t)

##

## Parameters:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## l 1.01e-02 7.76e-06 1308 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.00366 on 354 degrees of freedom

##

## Number of iterations to convergence: 6

## Achieved convergence tolerance: 2.7e-06

Again, the estimate for the mean dwell time of 98.6092 is close to the real value of 100.

Figure 5 shows the curve fits done so far in one graph for comparison. In this data set as well as several others the difference between the linear fit and the exponential fit is small. The fit to the linearly interpolated CDF data however appears to be less good.

Simulating a mixture of high and low affinity sites

Next, data for a mixture of a high affinity site (mean dwell time of 10s, 200 sites) with low affinity sites (mean dwell time of 1s, 1800 sites) is simulated using a similar process as above

set.seed(5620)

sim.2.data <- function() {

dt.2 <- c()

ti <- 1

n.la <- 1800

n.ha <- 200

pd.ha <- 1 - 100/101

pd.la <- 1 - 10/11

while (n.la + n.ha > 0) {

n.diss.la <- min(sum(runif(n.la) <= pd.la), n.la)

n.la <- n.la - n.diss.la

n.diss.ha <- min(sum(runif(n.ha) <= pd.ha), n.ha)

n.ha <- n.ha - n.diss.ha

dt.2 <- c(dt.2, rep(ti, n.diss.la + n.diss.ha) +

round(rnorm(n.diss.la + n.diss.ha, sd=1.5)))

ti <- ti + 1

}

dt.2[dt.2 < 1] <- 1

dt.2

}

dt.2 <- sim.2.data()

dt.2.cdf <- ecdf(dt.2)

dt.2.df <- data.frame(t = unique(dt.2))

dt.2.df$mcdf <- 1 - dt.2.cdf(dt.2.df$t)

dt.2.df <- subset(dt.2.df, mcdf > 0)

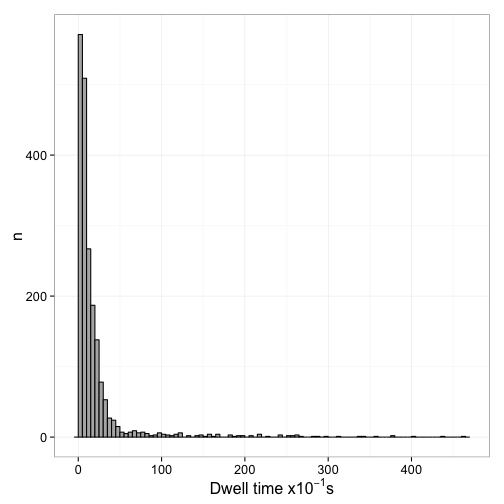

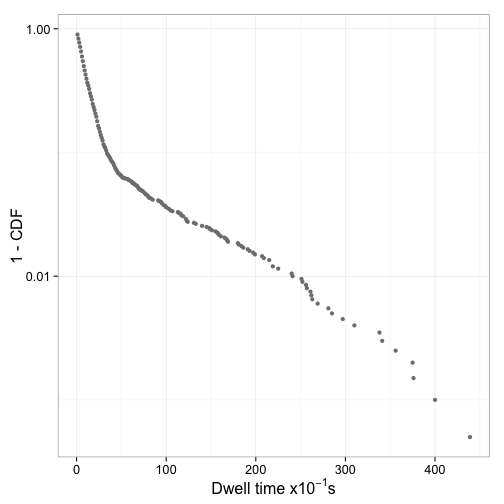

Figure 6 shows the distribution of dwell times and Figure 7 the log plot of 1-CDF of the dwell times

Fit mixed exponential model

The mixed exponential model that should be fit here is

\[n(t) = f_{ha}e^{-\lambda_{ha}t} + (1 - f_{ha})e^{-\lambda_{la}t}\]

This cannot be easily linearized. Therefore the exponential model

needs to be fit directly. Again we use nls. However, keep in

mind that there is no distinction between the two rate constants,

which means that either one of them might end up corresponding to

the high affinity sites.

expm.2 <- nls(mcdf ~ f * exp(- l1 * t) + (1 - f) * exp(-l2 * t),

data = dt.2.df,

start = list(l1=1/10, l2=1/2, f=0.5))

summary(expm.2)

## Formula: mcdf ~ f * exp(-l1 * t) + (1 - f) * exp(-l2 * t)

##

## Parameters:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## l1 0.009268 0.000234 39.6 <2e-16 ***

## l2 0.095546 0.000385 248.0 <2e-16 ***

## f 0.092851 0.001809 51.3 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.00334 on 143 degrees of freedom

##

## Number of iterations to convergence: 9

## Achieved convergence tolerance: 5.46e-07

The estimates of the mean dwell time of the high affinity sites (107.903), the low affinity site (10.4662), and the fraction of sites that are high affinity (0.0929) are close to the values used in the data generating process.

Is the two component model significantly better than a single component model?

expm.2.single <- nls(mcdf ~ exp(-l * t),

data = dt.2.df,

start = list(l=1/10))

summary(expm.2.single)

## Formula: mcdf ~ exp(-l * t)

##

## Parameters:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## l 0.07572 0.00125 60.3 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.0301 on 145 degrees of freedom

##

## Number of iterations to convergence: 6

## Achieved convergence tolerance: 3.8e-06

anova(expm.2.single, expm.2)

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Model 1: mcdf ~ exp(-l * t)

## Model 2: mcdf ~ f * exp(-l1 * t) + (1 - f) * exp(-l2 * t)

## Res.Df Res.Sum Sq Df Sum Sq F value Pr(>F)

## 1 145 0.1310

## 2 143 0.0016 2 0.129 5799 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

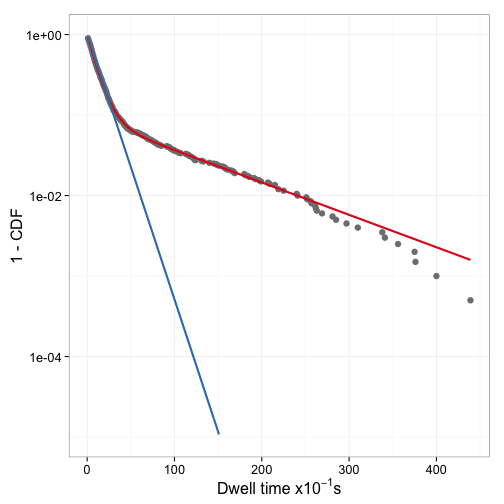

Indeed it is. Figure 8 shows the two fitted models with the data.

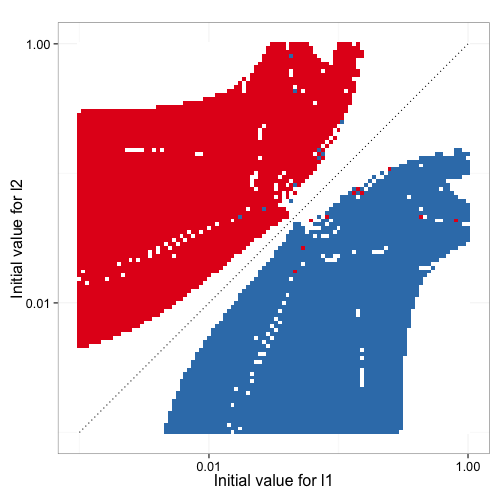

How dependent on the starting values are the results of nls? To find out,

nls is run with a range of starting values for lla and lha (fixing f

at 0.5).

fit.grid <- local({

eg <- expand.grid(start.l1=10^seq(-3, 0, length.out=100),

start.l2=10^seq(-3, 0, length.out=100))

eg$fit.l1 <- NA

eg$fit.l2 <- NA

eg$fit.f <- NA

for (i in 1:nrow(eg)) {

fit <- try(nls(mcdf ~ f * exp(- l1 * t) + (1 - f) * exp(-l2 * t),

data = dt.2.df,

start = list(l1=eg[i, "start.l1"],

l2=eg[i, "start.l2"],

f=0.5)),

silent=TRUE)

if (inherits(fit, "nls")) {

eg$fit.l1[i] <- coef(fit)["l1"]

eg$fit.l2[i] <- coef(fit)["l2"]

eg$fit.f[i] <- coef(fit)["f"]

}

}

eg$fit.lha <- pmin(eg$fit.l1, eg$fit.l2)

eg$fit.lla <- pmax(eg$fit.l1, eg$fit.l2)

eg$fit.fha <- ifelse(eg$fit.l1 < eg$fit.l2, eg$fit.f, 1-eg$fit.f)

eg

})

Figure 9 shows how the inital estimates for the parameters impact which of the two rate constants ends up estimating the high affinity sites and how many times the model fitting fails. Clearly the direction of the estimates and any estimates are possible at all heavily depend on the starting parameter estimates.

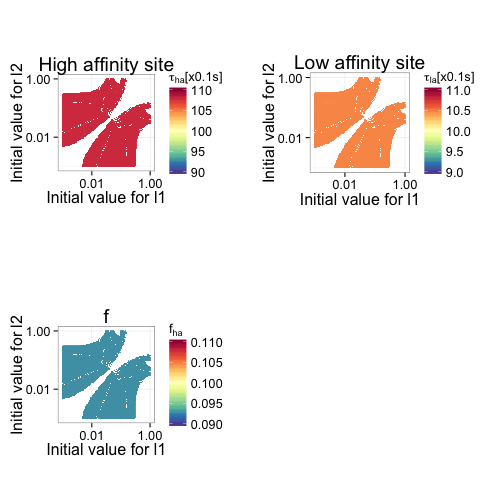

Figure 10 shows how accurate the fitted values for high affinity mean dwell time, low affinity mean dwell time, and fraction of high affinity sites are as a function of the initial estimates. It is clear that in this particular data set, the bias of the estimates is not dependent on the initial input data.

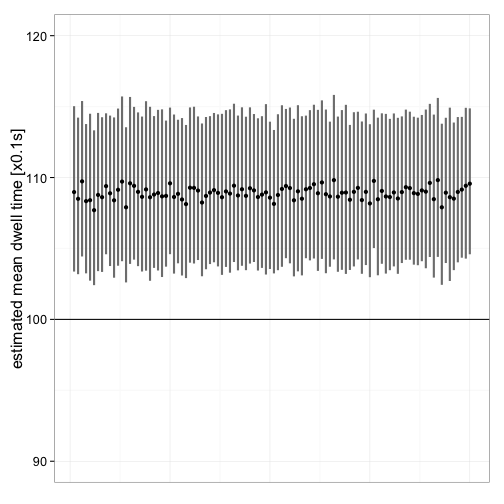

Another question is how good the estimates are for different data sets. So, 100 data sets are simulated and the estimates along with their confidence intervals are plotted. Initial values are selected based on the previous analyses. Figure 11 shows that the mean dwell time is consistently overestimated (rate constant underestimated), irrespective of data set. Despite the obvious bias, the difference is reatively small.

set.seed(3321999)

fit.rep <- list()

for (i in 1:100) {

tmp <- sim.2.data()

tmp.cdf <- ecdf(dt.2)

tmp.df <- data.frame(t = unique(tmp))

tmp.df$mcdf <- 1 - tmp.cdf(tmp.df$t)

tmp.df <- subset(tmp.df, mcdf > 0)

fit <- try(nls(mcdf ~ f * exp(- lha * t) + (1 - f) * exp(-lla * t),

data = tmp.df,

start = list(lha=1/30, lla=1/3, f=0.5)),

silent=TRUE)

if (inherits(fit, "nls")) {

fit.rep[[i]] <- fit

}

}

Final thoughts

- There appears to be a consistant bias in the estimates. In a future post i will try to determine where the bias comes from (or if there is a flaw in the simulated data).

nlsdefaults to the Gauss-Newton algorithm which is less stable with respect to initial estimates than Levenberg-Marquardt (LM).minpack.lmprovides the LM algorithm. In a future post i will comparenlsto the minpack implementation as well s thegnmpackage, which implements generalized nonlinear models.